At a meeting in Dublin on 11 August 2015, Amnesty International’s International Council adopted a resolution to authorise their International Board to develop and adopt a policy on “sex work”. Here is a quote from their press release:

“Sex workers are one of the most marginalized groups in the world who in most instances face constant risk of discrimination, violence and abuse.

The resolution recommends that Amnesty International develop a policy that supports the full decriminalization of all aspects of consensual sex work. The policy will also call on states to ensure that sex workers enjoy full and equal legal protection from exploitation, trafficking and violence.

“We recognize that this critical human rights issue is hugely complex and that is why we have addressed this issue from the perspective of international human rights standards. We also consulted with our global movement to take on board different views from around the world,” said Salil Shetty.” [emphasis mine]

The resolution calls not only for the decriminalisation all those involved in prostitution (which all feminist groups call for) but also for the decriminalisation of pimps, punters and brothel owners who are the main perpetrators of the violence and abuse against those in prostitution. This proposal is essentially for the legalisation of prostitution and the entire sex trade. (You can quibble about semantics but when something is not criminal it becomes legal.)

How Amnesty International went about developing this proposal and consulting on it was problematical. In this article I summarise some of the issues. Many others have written eloquently on why the policy itself is misguided (for example, Chris Hedges, Michelle Kelly and Catriona Grant). In this article I focus on the duplicitous nature of Amnesty’s actions. Please use the comments to add additional relevant information.

Links to Amnesty’s documents:

- The final resolution

- The draft policy that was circulated shortly before the August 2015 meeting

- An earlier version of the policy and a summary of some of the feedback they received

- The draft policy/background paper that was leaked in early 2014

1. Amnesty ignored international human rights treaties

Amnesty’s press release about the new resolution clearly states that Amnesty “addressed this issue from the perspective of international human rights standards”. However, this is simply not true. For example, Amnesty failed to mention or misrepresented key international human rights instruments, which underpin national human rights law:

The 1949 United Nations Convention on the Suppression of the Trafficking in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others

This states that “prostitution and the accompanying evil of the traffic in persons for the purpose of prostitution are incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person and endanger the welfare of the individual, the family and the community”. This therefore defines prostitution as incompatible with the UN Declaration of Human Rights 1948 which guarantees human dignity and integrity to all.

Amnesty failed to mention or consider this treaty, which defines prostitution as a violation of human rights. A key aspect of human rights is that consent to their violation is not relevant and does not nullify the violation.

Amnesty’s proposal to decriminalise those who buy sex and profit from the prostitution of others therefore seeks to legalise the violation of human rights guaranteed by the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

When prostitution is understood as a human rights violation, Amnesty’s entire proposal for the decriminalisation of “consensual sex work” is seen to be a dangerous fallacy.

The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (sometimes called the Palermo Protocol)

The United Nations adopted this protocol in 2000. It sets out the internationally agreed definition of human trafficking and puts a legal obligation on ratifying nations (the UK is one) to implement strategies to reduce the demand that leads to sex trafficking. Amnesty fails to mention this or that research has shown that decriminalisation of the sex trade (as they propose) inevitably leads to an increase in sex trafficking.

The early version of Amnesty’s policy said “Amnesty International believes that the conflation of sex work with human trafficking leads to policies and interventions which undermines sex workers’ sexual autonomy, and causes them to be targets of exploitation and abuse, as well as may enable violation of their human rights.”

However, the Palermo Protocol definition makes it clear that the essential feature of sex trafficking is third-party involvement in the exploitation of the prostitution of another. It does not require the movement of the person across international borders or even from place to place within a country. As Catharine MacKinnon memorably put it, “trafficking is straight-up pimping”.

When we consider that most women and girls in prostitution have a pimp – a third-party who exploits their prostitution – it comes as no surprise that Sigma Huda, UN Special Rapporteur on Trafficking 2004–2008, observed that “prostitution as actually practised in the world usually does satisfy the elements of trafficking”. See Sex Trafficking for more on this.

Amnesty’s proposal contradicts this important human rights treaty, contradicts nation state’s legal obligations in regards to sex trafficking, and recommends the decriminalisation of what are essentially traffickers (pimps).

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)

This broad United Nations treaty was adopted in 1979. It calls on states to end all forms of discrimination against women and girls. Countries that have ratified the treaty are legally bound to implement its provisions, which include considering the impact of all policies on gender equality and the health, status and well being of women and girls. Amnesty has failed to do this with its “sex work” policy proposals.

Prostitution is a profoundly gendered institution – more than 99.9% of buyers are male and globally more than 80% of those prostituted are female but Amnesty failed to even mention this or to consider how the status of all women is negatively affected when prostitution is legalised, nor the devastating impact that prostitution invariably has on the health and well being of the women and girls directly involved. Amnesty’s policy therefore recommends legislation that would contravene the legal obligations that states have under this treaty.

Amnesty’s background document (linked above) mentions CEDAW but only Article 6, which requires states to combat and suppress “all forms of traffic in women and the exploitation of the prostitution of others”. However, Amnesty’s concern seems to be only to argue that this does not require the criminalisation of punters.

Sweden, where the purchase of sexual services is criminalised on the basis that prostitution is incompatible with gender equality and the integrity of the person, describes their approach (referred to as the Nordic Model) as evidence of compliance with their obligations under Article 6. The CEDAW committee have agreed with this interpretation. (See the EVAW submission for more on this.)

2. Amnesty presented the arguments dishonestly

Amnesty presented the arguments in such a way that unless you were already well informed, you would get the impression that many people are calling for those involved in prostitution to be criminalised. However, in fact not a single feminist or human rights group or organisation working in the field is calling for this. This way of arguing is sometimes called a straw man argument and is often the sign of a poor argument or an ulterior motive. It is not the behaviour we would expect from an international human rights organisation.

Similarly Amnesty disguised the fact that they were calling for the full decriminalisation of the entire sex industry, including pimps, punters and brothel owners, behind phrases like “the operational aspects” of the industry and by lumping sex buyers and sellers together.

This means that Amnesty members and supporters were asked to make a decision on the basis of incomplete information presented in a dishonest and biased way.

3. The resolution is contradictory

Having presented the proposal as all about “sex workers” rights and about protecting and decriminalising “sex workers” it is extraordinary that the final point of the resolution includes the following:

“States can impose legitimate restrictions on the sale of sexual services”

That’s right! Amnesty says states can criminalise selling sex but not buying sex or the “operational aspects” of the industry! This is the exact opposite of what the human rights treaties mentioned above require for compliance and the exact opposite of what the survivor movement and many feminists are calling for. And the exact opposite of what Amnesty seems to be saying the proposal is about – making things safer for “sex workers”.

But given the proposal was originally written by a pimp, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised.

4. The first version of the policy was written by a pimp

If you think that Amnesty, a leading human rights organisation, developed the proposal from a position of protecting the most vulnerable parties – the women and children stuck in prostitution – you would be wrong. The original policy proposal, from which the resolution developed, was written by Douglas Fox, founder and business partner of Christony Companions – one of the UK’s largest escort agencies – i.e. a pimp who has a powerful vested financial interest in the decriminalisation of pimps and punters.

Here is an excerpt from the Official Hansard Report of the 30 January 2014 session of the Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Justice. Ms Teggart is from Amnesty International and Mr Wells is a committee member:

Mr Wells: Who else is Douglas Fox?

Ms Teggart: I will look to you for that.

Mr Wells: I think that you know who Douglas Fox is, do you not?

Ms Teggart: I think that, after your e-mail inquiry, based on what my colleague googled, he came up as an International Union of Sex Workers (IUSW) activist.

Mr Wells: Douglas Fox runs the largest prostitution ring in the north-east of England. He has been on the front page of ‘The Northern Echo’ and is quite proud of that fact. Douglas Fox was running the largest prostitution ring in the north-east of England, he was a member of Amnesty International, in one of your north-east branches, and he proposed the motion at your AGM in Nottingham in 2008. Is that correct?

Ms Teggart: He did not propose the motion. The motion was proposed by the Newcastle upon Tyne group.

Mr Wells: But he was instrumental in that motion, which went before your group.

Ms Teggart: He was a member of the group that brought forward that motion.

Mr Wells: You allowed a person who ran the largest prostitution ring in the north-east of England to have major input in your policy development.

- For copy of a memo Douglas Fox wrote about his involvement, see What Does the Fox Say… – A super-pimp’s strategy re: Amnesty International.

- For more information about Douglas Fox as a pimp, see: The Escort Agency (film)

- For an interview with Douglas Fox, in which he explains his contribution to the redefinition of pimps as “sex workers”, see “What you call pimps, we call managers.”

- For information about how Douglas Fox encouraged his sex trade associates to join Amnesty in order to influence policy, see Sex trade ‘was asked to join Amnesty and lobby internally’.

5. Amnesty’s position was decided in advance

The feminist journalist Julie Bindel obtained notes of an Amnesty International meeting held in the UK in 2013 that show that the International Secretariat (IS) had the clear intention of supporting the full decriminalisation of the sex trade prior to the consultation process. You can read it here: Exclusive: Amnesty International UK’s Stitch-Up Job?

Given that Amnesty’s International Secretariat had decided on their position in advance, it is not a surprise that their consultation was something of a sham.

6. The consultation was a sham

When the draft policy/background paper was leaked in early 2014, many survivor and feminist groups condemned the proposal. Members were then offered three weeks (2-21 April 2014) to provide feedback on the document, although most members did not receive notification of this and members are spread around the globe in more than 70 countries. It is not uncommon to give more notice for a birthday party.

Many survivor and feminist organisations also provided feedback, including Eaves and the UK-based End Violence Against Women EVAW (a coalition of women’s organisations, service providers, academics, survivors and feminists, which, bizarrely, Amnesty UK is a member of). This set out clearly the implications of the proposal for gender equality and women and girls’ health and safety, the relevant human rights treaties, and how the proposal was at odds with binding human rights obligations to tackle sex trafficking and consider gender equality and women’s and girls’ health and safety.

An internal Amnesty document dated 11 June 2014 summarised the feedback and included another draft of the policy. Of the 29 countries that responded, all supported the decriminalisation of those in prostitution but only 4 countries supported the full proposal and almost as many (3) called for the criminalisation of those buying sex, and more than twice as many (11) called for more consultation. The document does not, however, provide unbiased information about the arguments against the proposal received in the consultation – for example, arguments and evidence for the Nordic Model.

The final draft of the policy was released to members on 7 July 2015. Some of the more controversial text had been removed, such as the text in the previous versions that suggested that buying sex is a human right and that restrictions on the buying of sex amounts to a violation of the buyer’s human rights. For example, here is an excerpt from the draft policy that was leaked in early 2014:

“Sexual desire and activity are a fundamental human need. To criminalize those who are unable or unwilling to fulfill that need through more traditionally recognized means and thus purchase sex, may amount to a violation of the right to privacy and undermine the rights to free expression and health.”

It appears that this was removed because the consultation had shown this to be hard to justify. However, the other changes did not fundamentally alter the proposal to fully decriminalise prostitution including punters and the “organisational aspects,” by which they mean pimps and brothel owners. The new draft did not even mention the criticisms from feminist and survivor groups or research that shows that full decriminalisation leads to greater trafficking and child sexual exploitation, and arguments for the Nordic Model do not even get a mention, not even a reference. And every single reference provided supports their position. By omitting the large body of writing and research that shows an opposing position, they gave a very one-sided and biased view.

On page 9, they dismiss criminalisation of buying sex like this:

Bans on buying sex can lead to sex workers having to take risks to protect their clients from detection by law enforcement, such as visiting locations determined only by their clients26.

And the reference to back this up is:

26 See: Criminalisation in Norway. See also: Bjørndah,l U. Dangerous Liaisons: A report on the violence women in prostitution in Oslo are exposed to. Oslo, 2012. Vista Analyse, Evaluering av forbudet mot kjøp av seksuele tjenester 2014 (English Summary- available at: http://vista-analyse.no/site/assets/files/6813/eng1.pdf)

Which sounds great. Except that the Dangerous Liaisons report was based on misrepresentation of the research, which actually showed that the introduction of the Nordic Model in Norway had in fact reduced violence. See New research shows violence decreases under Nordic model: Why the radio silence?

Many organisations, including survivor groups (such as Space International) and feminist groups criticised Amnesty’s new draft policy. The Coalition Against Trafficking of Women (CATW) published an open letter signed by over 400 advocates and organisations, condemning “Amnesty’s proposal to adopt a policy that calls for the decriminalization of pimps, brothel owners and buyers of sex — the pillars of a $99 billion global sex industry.”

Contrary to claims that decriminalisation would make prostituted people safer, critics pointed to research from numerous countries in which deregulation of the sex industry had produced catastrophic results: “the German government, for example, which deregulated the industry of prostitution in 2002, has found that the sex industry was not made safer for women after the enactment of its law. Instead, the explosive growth of legal brothels in Germany has triggered an increase in sex trafficking.” These campaigners instead asked Amnesty to support the so-called Nordic model, in which sex buyers and pimps are criminalised, while prostituted people are decriminalised and provided with services to help them exit. Former President Jimmy Carter set up a petition advocating Amnesty to adopt a Nordic Model approach.

What is the point of a consultation if you ignore the responses you get?

7. Listening to “sex workers” – but only if they agree

In the run up to the vote in Dublin on 11 August 2015, Amnesty emphasised the importance of listening to “sex workers”. But what does that mean when, as Douglas Fox explained in his interview with Julie Bindel and Cath Elliott, many pimps and brothel owners describe themselves as “sex workers”? And, as Raquel Rosario Sanchez eloquently explains in How to manufacture consent in the sex trade debate, people who describe themselves as “sex workers” are, almost by definition, in favour of decriminalisation of the sex industry.

There is a large international movement of survivors of prostitution who reject the terms “sex work” and “sex worker” because these terms are euphemisms that obscure and sanitise an abusive and rapacious industry, they incorrectly imply that prostitution is work like any other, and, as mentioned, the term often includes pimps and brothel owners. Amnesty appears to have deliberately ignored the voices of these survivors. And also of the women in prostitution who do not agree with full decriminalisation.

Most people in prostitution are marginalised and ignorant of the possible approaches, including of the Nordic Model. Chelsea, a prostituted woman in New Zealand, said the following about Amnesty’s approach:

“I’m a prozzie myself and I have never met another one who wants our pimps and johns to be decriminalized, or who wants to be made to pay tax on top of what the pimps already take, and to be given zero social services that help us to exit, rehabilitate ourselves, get an education and a real job for the future and instead to just be told its perfectly acceptable for us to stay right where we are. None of us want that, even those of us who are here by “choice” because we need the money. We all want it to be temporary. We all would leave immediately if we could.

Most of us are uninformed about government policies and have never heard of the Nordic Model so we might support decriminalization but only because we think the alternative is for us to be criminalized and arrested along with our abusers. Everyone who knows about the Nordic Model supports it. I would give my life to bring the Nordic Model to my country, not that it’s much of a life to give.”

8. Amnesty’s proposal is based on a false premise

The sex industry is a $99 BILLLION money making machine. It requires a continuous stream of new blood – because women get used up and men demand new faces. But women who have real choices – for example, for decent well-paid work in the computer industry, medicine, nursing, banking or academia – do not usually choose prostitution. Prostitution is not on the menu of career options given to girls from comfortable middle class homes.

So the sex industry has a problem. How does it meet the demand from men, the demand that leads to their profits?

In Choice in an Unequal World, I show how poverty, destitution, child abuse and our over sexualised culture drive many girls and young women into prostitution. This is a form of coercion. Other forms of coercion are more overt: Traffickers and pimps kidnap girls in poor countries or lure them with promises of nice jobs in catering and childcare. Or they go to poor communities in rich countries and look for disaffected girls, women and girls with insecure immigration status, homeless women and runaway girls, single mothers who can’t make ends meet, and capture, lure and groom them. And once the pimps have them, they go to lengths to make sure they are trapped. They knock them about or lock them up or get them addicted to hard drugs so they have to keep going to feed their habit.

This is the reality for the vast majority of women and girls in prostitution worldwide.

Now consider Amnesty’s definition of sex work:

“Sex work involves a contractual arrangement where sexual services are negotiated between consenting adults, with the terms of engagement agreed between the seller and the buyer of sexual services. By definition, sex work means that sex workers who are engaging in commercial sex have consented to do so, (that is, are choosing voluntarily to do so), making it distinct from trafficking. Sex work takes many forms, and varies between and within countries and communities. Sex work may vary in the degree to which it is more or less ‘formal’ or organised.” [my emphasis]

This definition does not reflect the material reality of the vast majority of women and girls in prostitution or the extreme imbalance of power between the punter and the prostituted woman or girl. This definition also shows a misunderstanding of trafficking – that it is a human rights violation for which consent is irrelevant. This definition is the wishful thinking of those in denial or with a vested interest.

To acknowledge the reality of the forces that are stacked against the women and girls in prostitution does not deny their agency and resourcefulness and to suggest it does is an insult to everyone’s intelligence.

Amnesty’s entire proposal is based on this definition – on the idea that prostitution is an agreement between two equally-placed individuals who are consenting to a business arrangement. And while it is possible that there is a small minority for whom this is true, in practice it is not possible to separate this small minority from the vast majority for whom coercion of one form or another is the reality.

9. Conflicts of interest

As mentioned earlier, there is evidence that pimps and others who profit from the sex trade have joined Amnesty in order to influence its policy on prostitution. But there are other powerful vested interests at play. Amnesty receives significant funding from George Soros and the Open Society Foundation, both of whom lobby for the decriminalisation of the sex industry. For more about this powerful financial conflict of interest, see NGOs: the best PR and Spin Doctors that (sex-industry) money can buy.

In addition there is evidence that Amnesty has received funding from governments, including the UK and US governments, both of which support the neoliberal project of maximising profits at more or less any cost and extending the market into every aspect of our lives, including the sexuality that is at the core of our humanity, and whose austerity policies have led to widespread and devastating poverty (which in turn drives women and girls into prostitution and boys and young men into pimping).

But the conflict of interest goes deeper than funding. It goes to the root of the relationship between the sexes in our patriarchal capitalist society. In Prostitution – Calling for a New Paradigm, I show how prostitution is one of the keystones of the patriarchal system that keeps men on top and women subordinated. Like most large organisations, Amnesty is dominated by men. Gita Sahgal, the former head of Amnesty’s gender unit, spoke of its misogynist leadership after she was suspended.

Men, as the beneficiaries of the patriarchal system have a vested interest in maintaining prostitution and the sex industry. Frankly the men who rule Amnesty International (and indeed all men) should listen to women on this matter. And not just the women who agree with you (and the women who are dependent on you, such as the young women with junior positions within Amnesty itself) but also women who don’t, like survivors of prostitution and radical feminists.

“When women’s bodies are on sale as commodities in the capitalist market, the terms of the original contract cannot be forgotten; the law of male sex-right is publicly affirmed and men gain public acknowledgement as women’s sexual masters – that is what is wrong with prostitution.” (Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract)

10. Amnesty’s research was flawed

Amnesty conducted research in 4 countries (Papua New Guinea, Norway, Argentina and Hong Kong) that have a variety of legislative approaches to prostitution, including one country (Norway) that has implemented the Nordic Model. Amnesty did not make the full reports publicly available but the leaked final draft policy includes a summary of the “overarching” research findings. This states that they interviewed “80 sex workers” – i.e. an average of 20 in each of the four countries, which is too small a sample to draw conclusive results. Also, as we saw earlier, the “sex worker” term may include pimps and others with vested interests in the decriminalised approach that Amnesty recommends.

The research purports to show “the human rights impact of criminalisation of sex work.” However, they did not conduct research in a country (like Holland or Germany) that has implemented a fully decriminalised approach. To show that full decriminalisation is the solution to the problems that they observed, they would need to show that these problems are not present in countries that have implemented that solution.

Under the heading “Criminalisation of sex work compounds stigma and discrimination against sex workers”, the research summary includes four quotations from migrant women in street prostitution in Norway describing racist slurs they had received from passing white Norwegian women. Clearly what these women describe is appalling but it does not prove that it is caused by the prostitution legislation or that it would be solved by decriminalisation.

Under the heading “Sex workers are criminalised and negatively affected by a range of sex work laws – not just those on the direct sale of sex,” there are several quotations from women in prostitution in Norway who complain that the ban on sex buying results in them having to visit clients in their homes and the dangers this involves. For example:

“When you go to a customer’s house there could be five of them there.”

“If he hurts you there is no-one there to rescue you.”

Rather than proving that decriminalisation is the solution, this shows that punters are inherently dangerous to women in prostitution and that the prostitution relationship is inherently unequal. That Amnesty wants to legitimise this inherently dangerous and unequal relationship through full decriminalisation of the entire industry seems to prove only that it has lost touch with its original aims of protecting the least powerful.

Under the heading “Criminalisation gives police impunity to abuse sex workers and acts as a major barrier to police protection for sex workers,” the summary says that Amnesty “did not find substantive evidence of police violence towards sex workers in Norway.” Unfortunately they did not conclude from this that Norway’s Nordic Model legislation has produced some good results for prostituted women in Norway. The report goes into some detail about how a law against promoting prostitution in Norway is used by the police to evict prostituted women from their accommodation. However, again this does not prove that the full decriminalisation that Amnesty is advocating is the only solution or even a solution. You do not have to be a genius to think of other solutions.

Under the heading “The most marginalised sex workers often report the highest levels, and worst experiences, of criminalisation,” the summary reports migrant on-street prostituted women in Norway complaining of racism from the police and the public. However, there is no evidence that this is related to the Nordic Model law per se or that full decriminalisation of the sex industry would magically cure the racism in this Scandinavian society.

The summary also reports the head of a Brazilian transgender rights NGO saying that the police demand money to protect the prostituted transgendered people from human trafficking networks and thieves. Again this does not prove that full decriminalisation of the sex industry would solve this problem. However, it does hint at the extreme dangers that prostituted people experience from those who profit from the sex trade.

There is no doubt that marginalised people are treated appallingly in the sex trade. The argument is about what is the best way to deal with this. There is a significant body of research that shows that prostitution tends to entrench the disadvantages that marginalised people face. This is an argument for the Nordic Model rather than for full decriminalisation of the entire industry.

It is clear that Amnesty’s research was poorly designed and implemented and it is not possible to honestly extrapolate from the research that full decriminalisation of the industry would be a solution to any of the problems that they document. This suggests that the research was not conducted in good faith and a spirit of openness but with the aim of proving what had already been decided.

A more honest approach would be to compare a country that has implemented a fully decriminalised approach (such as Holland) with a country that has implemented the Nordic Model. Sweden would make the best choice as an example of a country that has implemented the Nordic Model, as it has the longest experience with that approach and has had time and, importantly, the political will to iron out some of the teething problems.

11. Amnesty is silent on how to address trafficking and child sexual exploitation

Amnesty’s resolution mentions the obligation that states have to prevent and combat sex trafficking and child sexual exploitation. But they are silent about how states should go about this. This is a huge and glaring omission.

The reality is that sex trafficking and child sexual exploitation are driven by the enormous profits that can so easily be made. The profits come because large numbers of men are prepared to pay large amounts of money to buy (mainly) women and children for sex. In the UK we regularly hear that traffickers and pimps sell girls and young women for £500-£600 an hour.

Anything that legitimises prostitution inevitably leads to an increase in this demand from men.

Rachel Moran has written eloquently on prostitution as the commercial value of youth, that the commonest question on brothel phone lines is always “What is your youngest girl?” and how the very idea that there is a separation between the prostitution of adults and children is flawed given that most start as children (internationally defined as under 18 in respect to prostitution).

Finland and England have criminalised the buying of sexual services from someone who has been subjected to force, threat or coercion. This was introduced in England in the Policing and Crime Act 2009. The maximum penalty is a level three fine. However, this is not an effective approach.

In 2012-2013 there were eight prosecutions in England and Wales. There are thousands of victims of trafficking in the UK and each victim sees hundreds of punters each year. Suppose we take a conservative figure that there are 10,000 women who fulfil the criteria of being subject to some form of force, threat or coercion and suppose each of these women sees 200 punters a year (almost definitely an underestimate, but some of them will visit more than one woman). This makes a total of 2,000,000 potential offenders. And in a year they prosecuted eight. To prove that the woman has been forced, threatened or coerced to meet the “beyond reasonable doubt” test of the criminal court requires significant policing resources. But the offence itself carries a low penalty and the police do not therefore justify investing sufficient resources to police this crime. (For more on this, see Sex Trafficking.)

This then is another argument for the Nordic Model, in which buying sex is made a crime per se, regardless whether the prostituted person was coerced or not. This makes the offence much easier to police and gain convictions – which in turn makes it possible to actually enforce, so that it acts as a real deterrent, because the real possibility of being caught and exposed is the thing that men say is most likely to deter them. This in turn reduces the demand that drives the traffic in women and children for the exploitation of their prostitution and enables the state to meet their legal obligations to reduce the demand for sex trafficking.

12. Amnesty lied about who they’d consulted

In an email response to a protest about Amnesty’s proposed policy, Jackie Hansen, Major Campaigns and Women’s Rights Campaigner, Amnesty International Canada said the following:

“Internationally, Amnesty International has held discussions with hundreds of organizations and many more individuals including, but not limited to, International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe – ICRSE; The NGO Delegation to the Programme Coordinating Board (PCB) of UNAIDS; Freedom Network; The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, Australia; The Resource centre for women (Marta), Latvia; Ruhama, Ireland; Center for Reproductive Rights; Global Network of Sex Work Projects; SPACE International (Survivors of Prostitution-Abuse Calling for Enlightenment); Equality Now; Rape Crisis Network Ireland (RCNI); SANGRAM India; Abolish Prostitution Now.”

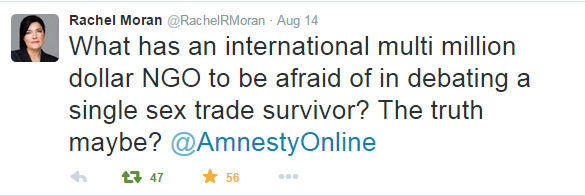

Rachel Moran, survivor of prostitution and co-founder of SPACE International, confirmed in a tweet that in spite of pledging to consult with them in a Committee for Justice Meeting of the Northern Ireland Assembly on 30 January 2014, Amnesty did not in fact consult with SPACE International.

Resources Prostitution, a feminist campaigning organisation, confirmed in a tweet that after months of calling Amnesty begging to talk to them about their proposals, Amnesty responded after the crucial vote on 11 August.

Shortly after Amnesty voted on the issue, Rachel Moran was asked to appear on the BBC’s “The World This Week” to debate with Amnesty. She agreed but Amnesty refused to debate directly with her and insisted that the show was segmented so that Rachel would speak first and they would follow. They refused to meet Rachel Moran in a head on discussion.

What has Amnesty got to be afraid of in talking to a single survivor of prostitution, except perhaps the truth?

13. So what should Amnesty do now?

It is not too late for Amnesty to admit that it has made very many very serious mistakes in this matter, not least in allowing itself to be influenced by powerful vested interests. And it is not too late for Amnesty to abandon its current proposals. I sincerely urge Amnesty to do this as a matter of urgency.

Notes

| Date | Notes |

|---|---|

| 15 September 2015 | For an Italian version of this article, see Le voci delle sopravvissute che Amnesty non ha voluto ascoltare. |

| 28 September 2015 | For a response to this article from Terry Rockefeller on “behalf of the Board and the Priorities Subcommittee” sent to an internal Amnesty International USA discussion forum, plus some observations of my own, see Amnesty’s Response. |

| 28 September 2015 | For 120 questions that Amnesty needs to answer before going any further with this, see 120 Questions for Amnesty. |

| 15 October 2015 | Kat Banyard has exposed that Alejandra Gil, the Vice President of the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) has been jailed for 15 years for trafficking. In 2009 the NSWP was appointed co-chair of UNAIDS and advised on their prostitution policy. Both NSWP and UNAIDS were referenced by Amnesty in its draft policy. See A Human Rights Scandal for more information. |

| 5 November 2015 | Claudia Brizuela, a former leader of Asociacion de Mujeres Meretrices de Argentina (Association of Women Prostitutes of Argentina)(AMMAR) and a founder of the Latin American-Caribbean Female Sex Workers Network, was arrested and charged for sex trafficking a year ago. The latter network was also represented by Alejandra Gil in Mexico, also found guilty of sex trafficking this Spring. Both groups were funded by UNAIDS and referenced by Amnesty International in support of the policy. See Ex dirigente de Ammar procesada por liderar red de trata. |

64 thoughts on “What Amnesty Did Wrong”